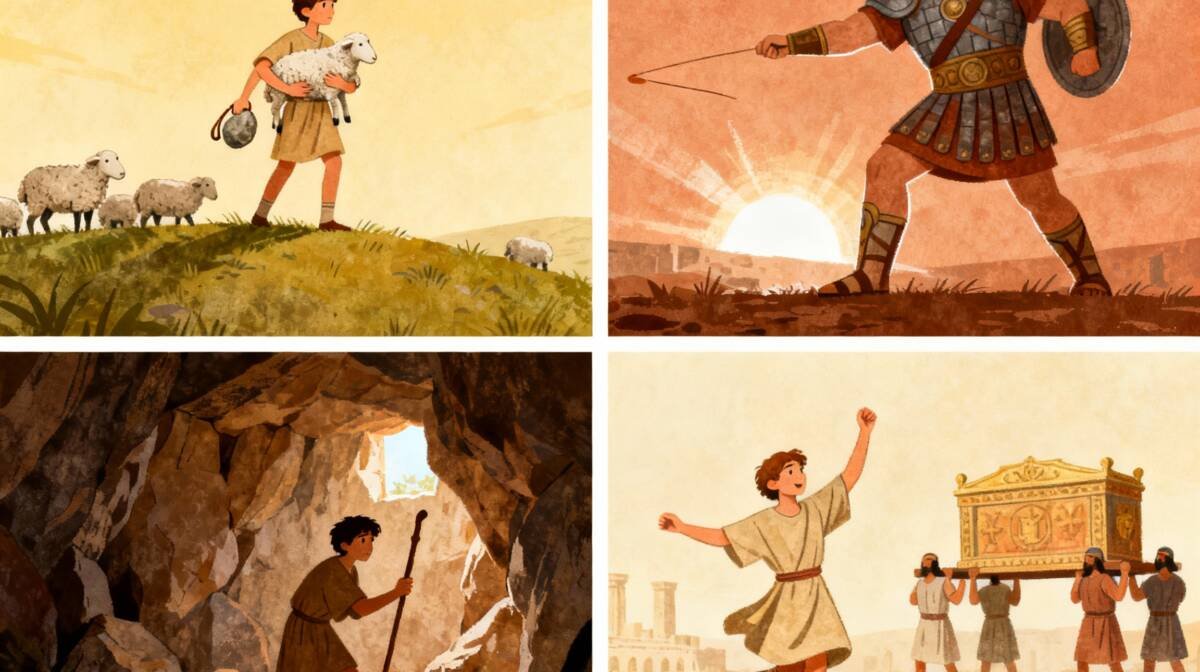

The Story of David

The Pasture: Alone with the Sheep

Morning arrives as a pale ribbon across the hills, and David is awake before the flock stirs. He moves among the animals counting in a whisper first the jumpy yearlings, then the mothers heavy with milk, then the ones whose hooves chip easily on limestone. A shepherd learns every sound a flock makes when it is well and the one sound it makes when something is wrong. He hears the sparrows, the wind through broom bush, the pop and sigh of a dying ember; he hears the unnatural hush that sometimes falls like a hand over a mouth. That is the silence that sends him moving, sling loose in one hand, staff in the other, prayer already forming. The pasture is not safer because a shepherd is there. It is safer because a shepherd refuses to leave.

The sun climbs and the day burns bright. He seeks water first, then graze, then shade and not just for comfort. Sheep panic when thirsty, crowding and trampling; calm has to be arranged. The sling is a simple friend, a length of leather that teaches attention. David practices until attention becomes instinct, until he can send a stone to nick the air inches from a straying ewe’s nose and turn her without bruising her. He is learning not just aim, but restraint. The sling will later stand between a nation and a taunting giant, but first it stands between a lamb and a cliff.

Evening falls like a blessing, and the cold arrives with it. He builds a small fire and sings the kind of songs that barely reach the stars. These are not court songs or battle anthems; they are the songs of a boy speaking to the One who watches him watch sheep. There are nights when the flock is quiet and his fingers find worship as easily as breath. There are other nights.

On those nights he hears the wrong silence, then the wrong footfall. The flock bunches. A blur like moving dusk explodes from the brush muscle and hunger and heat. The lion doesn’t roar; it steals. A lamb vanishes in a spray of dust. The shepherd runs before he has time to feel afraid. He follows the crash and snarl, stone already in the sling’s cradle. The throw is one motion step, sweep, release and the stone kisses the skull behind the ear. The lion turns, eyes yellow and astonished, and now the staff matters. The fight is close and ugly and loud. When it ends, David is shivering, breath coming in saw-toothed pulls, fingers sticky. He gathers the lamb, stunned and bleeding, and carries it back to the circle of light. He has learned something about fear. He has learned something about faith. He has learned that love does not negotiate with predators.

There are other nights when the enemy is a bear, the battle heavier, the ground torn by claws. Those rescues scar his forearms and his mind with a new kind of memory: deliverance. Later, when a king asks what business a boy has on a battlefield, David will answer with these nights. “Your servant kept his father’s sheep,” he will say, and when a lion or bear came and took a lamb, “I went after it… and when it rose against me, I caught it by the beard, struck and killed it.” The pasture is his résumé. His reference is the God who met him there.

The Valley of Elah: David and Goliath

The valley is a stage between two ridges: Israel on one, Philistia on the other. The champion steps into the low ground like a storm in bronze tall as dread, loud as blasphemy layered in metal that drinks the sun. His name is Goliath of Gath, and he has learned how to turn fear into a weapon you can hear. His voice crosses the valley and climbs the ridge to lodge under the ribs of every soldier who knows the math of war and the weight of his own armor. “Choose a man,” he says, and the air laughs with him. No one moves.

David arrives with bread and questions. He hears the taunt and tastes the old metal of the pasture again the taste of danger and zeal. To him, the insult is not against Israel only; it is against the living God who saved a lamb from a lion’s mouth and a boy from a bear’s embrace. Cynics call it youth. David calls it memory. Soldiers tell him to be quiet; brothers tell him to go home; the king tells him to dress like someone else. Saul’s armor hangs on him like a borrowed lie. He takes three steps and feels the truth: he cannot fight inside another man’s courage. He returns the armor with respect, not contempt, and goes looking for stones.

He knows where the water slows and drops its roundest gifts. He fingers the stones as if reading a familiar script weight, balance, promise and chooses five. Not because he doubts one will do, but because preparation is not doubt. He steps into the valley, and the giant laughs because that is what giants do when they see what faith looks like from far away. David runs. He does not creep or tiptoe or lunge. He runs. The sling arcs and sings; the stone flies truer than mockery. It finds the thin place the helmet does not guard, the soft target arrogance often leaves uncovered. The giant falls, and the ground answers with a sound David will hear for years the collective gasp when a nation remembers it has a God.

The boy crosses the distance that fear had opened and finishes the fight. The field changes sides, the Philistines scatter, and the song that starts on this day will follow David into caves, courts, and coronations. Yet the lesson remains stubbornly simple: the same God who trains hands in obscurity steadies hands in public. The battle was never sized by height; it was sized by trust.

Citations

David’s defense of the flock against lion and bear; David’s words to Saul: 1 Samuel 17:34–36, multiple translations and commentaries agree on the core details.

David and Goliath narrative across 1 Samuel 17, including David rejecting Saul’s armor, selecting five stones, and striking Goliath: 1 Samuel 17, NIV.

David’s recollection of God’s deliverance in the pasture applied to the battlefield: 1 Samuel 17:34–37.

The Caves: Anointed but Hunted

The oil on David’s head had long since dried, but the memory of it still glowed. He had been told he would be king; now he lived like a criminal. One day he had palace music and royal favor, the next he had spears flying past his face and orders stamped with his death. The path from promise to fulfillment bent not through comfort but through caverns.

En Gedi smelled of rock and wild goats and the kind of damp that never quite lets a cloak dry. David and his men pressed into the shadows of a cave, hearts pounding, trying to quiet their own breathing. Then they heard another sound: footsteps, alone, unhurried. A silhouette against the light at the mouth of the cave. Saul. The very man who hunted him had chosen, unknowingly, to rest where David hid.

Whispers circled through David’s men like a spark through dry grass. “This is the day,” they insisted. “God has delivered your enemy into your hand.” Their logic was perfect; their theology was nearly so. The king who wanted David dead was now unguarded, weapon laid aside, robe loosened. One stroke could end the running, end the fear, end the waiting. David crept forward, knife in hand, as the cave watched.

Steel kissed fabric. A corner of royal cloth fell away soundlessly into David’s grip. It would have been so easy to make the cut deeper. But as he moved back into the dark, his conscience cut him instead. The hem in his hand felt heavier than a sword. “I will not stretch out my hand against the Lord’s anointed,” he whispered, loud enough for his men and his own heart to hear. The same restraint that had once kept a stone from a sheep’s flesh now kept a blade from a king’s. David chose reverence over revenge.

When Saul left the cave, David followed at a distance, holding the piece of robe high. His voice shook the valley more than any war cry: “My lord the king!” Saul turned, startled, and saw the proof David had been close enough to kill him and had not. Tears cut lines through dust on the older man’s face. For a fragile moment, sanity and humility returned to Saul. “You are more righteous than I,” he admitted. It did not last, but the record did. Heaven had seen. So had David’s men. Leadership, they learned, is not only the power to strike but the power to spare.

The caves multiplied. One gave way to another, to deserts and strongholds and nights when David asked why the God who had promised him a throne now gave him only rocks for pillows and fugitives for company. Yet those same caves became classrooms of dependence. Songs were born there that would later be called psalms poems that dragged fear into God’s presence instead of hiding it. The man who once ran toward Goliath now ran toward God with his questions. Anointing without character is a tragedy; caves carve character.

Years later, the chase ended. Saul fell in battle, and the kingdom slowly, painfully, turned toward David. But the caves never quite left him. Their lessons trailed him into the palace: wait for God’s timing, honor even flawed authority, and never trust a shortcut that requires you to become what you hate.

Jerusalem’s Rooftops: Bathsheba and Uriah

Spring came again, the season when kings normally rode to war. This time, David stayed home. He had generals now, armies well-trained, borders mostly secure. The urgency of the early years had cooled into routine. Sometimes the most dangerous moment is not when everything is hard, but when most things are easy.

One evening, the city below him hummed with the soft sounds of domestic life pots, laughter, low conversations carried on the breeze. From his rooftop, David saw further than anyone else in Jerusalem. He saw courtyards, walls, and then her: a woman bathing, unaware of the eyes above her. Light traced the water over her shoulders. Desire arrived quickly, uninvited, and David let it sit down instead of sending it away.

He asked who she was. The answer came back with a warning wrapped inside: “She is Bathsheba, the wife of Uriah.” Not just any man Uriah the Hittite, one of David’s seasoned warriors, a name from the roll of the brave. The words “wife of” should have ended the conversation. They did not. David, who had once refused to take a shortcut to the throne, took one now to pleasure. He sent messengers. She came. They slept together. Later she sent a message of her own, only two words deep with consequence: “I’m pregnant.”

Panic wears many disguises. For a king, it can look like strategy. David summoned Uriah home from the front. He greeted him with questions about the war and then with a friendly suggestion: “Go down to your house. Wash your feet. Rest.” Under the words lurked a hope: if Uriah went home, shared his wife’s bed, the pregnancy could be pinned to him, not to David.

But Uriah carried a different code in his chest. He slept at the entrance of the palace with the servants, refusing to go home while the ark and his comrades camped in open fields. When David questioned him, Uriah’s answer sliced the air: how could he enjoy comfort while his brothers risked their lives? The contrast was brutal. The soldier from the front line showed more integrity than the king on the rooftop.

David tried again. He fed Uriah, poured him wine, nudged him toward drunkenness, thinking lowered inhibitions might open the path to Bathsheba’s door. Even then, Uriah slept with the servants. When manipulation failed, sin turned murderous. In the morning, David wrote a letter to Joab, his commander. The words inside were cold and precise: put Uriah at the fiercest point of battle, then pull back from him so he will be struck down. He sealed it, handed it to Uriah, and sent him back to the field carrying his own death warrant.

The plan worked. Arrows flew, men fell, Uriah among them. A messenger returned to Jerusalem with the report battle, retreat, casualties, and then the line David waited for: “Your servant Uriah the Hittite is dead also.” David dismissed the loss with a platitude about swords devouring one as well as another and sent the messenger back to “encourage” Joab. When Bathsheba finished mourning, he brought her into the palace as his wife. She bore him a son. The cover-up was complete.

Except it wasn’t. Heaven had watched the rooftop, the letter, the battlefield. Earth heard silence; God heard blood. The story closes its chapter with a single sentence that weighs more than all David’s excuses: the thing he had done displeased the Lord. The shepherd who had once risked his life for a lamb had sacrificed a man for his sin. The man after God’s own heart had wandered far from that heart. Yet even here, the story is not over.

Nathan’s Parable: Truth with a Mirror

God’s response did not arrive first as thunder or plague, but as a friend with a story. Nathan walked into the palace carrying courage and a parable. He did not begin, “You sinner.” He began, “There were two men in a city…” One was rich, surrounded by many flocks. The other was poor, with only one little ewe lamb he had raised like a daughter, letting it share his food, drink from his cup, sleep in his arms. One day a traveler came to the rich man, and instead of taking from his own abundant flock, the rich man seized the poor man’s only lamb and prepared it for dinner.

David listened, and the old shepherd in him roared awake. Rage flared. “The man who did this deserves to die!” he declared. “He must pay for that lamb four times over, because he did such a thing and had no pity.” The king had just passed sentence on himself without knowing it.

Nathan’s next words cracked the palace air: “You are the man.” In that moment, all the distances David had built between himself and his sin, between his choices and their cost collapsed. Nathan spoke for God, reminding David of all the gifts he had received: a kingdom, protection from Saul, houses, wives, honor. With all that, why had he despised the word of the Lord and taken what was not his? There would be consequences: violence would rise inside his own house; the child conceived in sin would not live.

David did not argue. He did not blame Bathsheba, or stress, or success. He did not fire Nathan or silence him. He said the only true sentence a broken heart can say: “I have sinned against the Lord.” The confession did not undo the damage, but it reopened the relationship. Out of this collapse came one of the Bible’s most searing prayers of repentance, a cry for a clean heart, a steadfast spirit, a joy restored. David would walk with a limp in his family and kingdom from this point, but he would walk it with God, not away from God.

Grace in this story is not soft. It does not pretend the rooftop never happened. It does, however, insist that even kings are not beyond confronting, and even adulterers and conspirators are not beyond forgiveness when they bow low enough. David’s life from here on carries both scar and song.

The Ark’s Procession: Undignified Joy

Years and battles later, another procession wound its way toward Jerusalem not an army this time, but the ark of God. The ark stood for God’s presence and covenant; bringing it to the capital meant putting worship at the heart of national life. David wanted this moment to be beautiful, but his first attempt went terribly wrong. The ark was placed on a new cart, drawn by oxen, rolling toward the city. When the oxen stumbled and the ark lurched, a man named Uzzah reached out to steady it and fell dead on the spot.

The celebration shattered. David was angry and afraid. He suddenly saw how lightly he had treated what was holy, how treatment of God’s presence had slipped into convenience rather than obedience. The procession halted. The ark stayed instead at the house of a man named Obed-Edom, and over time reports spread that everything in that house flourished. Blessing traced the box’s footprint.

Eventually, David tried again this time with reverence. Priests carried the ark on their shoulders as the law had prescribed. Every six steps, the entire company stopped to offer sacrifices. Six steps, stop, altar. Six steps, stop, blood and gratitude. The road to Jerusalem became a stitched line of worship. The king who had once rushed ahead of God now insisted on walking with God, slowly, deliberately, praise laid down under every seventh footprint.

As the ark drew near the city, music broke loose trumpets, shouting, singing and David lost self-consciousness in the joy. He wore a simple linen garment, trading royal robes for something closer to a servant’s outfit. Then he danced. Not the measured movements of a rehearsed ceremony, but the full-body, breathless abandon of a man who knows he has been spared and restored more times than he can count. His leaps and spins said what words could not: “All that I am, all that I have, belongs to You.”

From a window above, Michal watched, her eyes narrowing. To her, this was not worship; it was humiliation. A king should be composed, distant, majestic. Later, she confronted David with biting sarcasm about how “distinguished” he had made himself, uncovering in front of servant girls. David answered with something like steel wrapped in humility: he was dancing before the Lord who had chosen him, and he would become even more undignified than this if that’s what it meant to honor God.

That day drew two kinds of lines: one up the center of the street, where a king spun free in gratitude, and one up the side of a palace wall, where a queen stood still in contempt. The story does not forget which side it blesses. David’s nakedness was not about exhibition; it was about a refusal to let status stand between him and sincere worship. The same man who had once failed so terribly now refused to let shame, pride, or royal decorum keep him from expressing love to the God who had carried him through pastures, valleys, caves, courts, rooftops, and rebukes into this moment of presence.

Aftermath: A House with a Sword Hanging Over It

The palace did not go quiet after Nathan left. The prophet’s words stayed in the walls like an echo: the sword would not depart from David’s house, and the child born from his union with Bathsheba would die. David had been forgiven “You shall not die” but forgiven did not mean exempt from consequence. The man who once held another man’s death letter in his hand now held a sentence over his own family.

The baby boy was born, fragile and loved. When he fell ill, the king who had been passive on the rooftop became desperate on the floor. David stopped eating. He lay on the ground, night after night, pleading with God. Servants tried to raise him; he refused. He knew he could not undo what he had done, but he hoped he might at least bend the outcome, that perhaps mercy might spare the child if the father would fast and weep enough. Every breath became a prayer of “please.”

Then the house changed tone. Whispering, shuffling feet, servants who wouldn’t meet his eyes. They feared telling him what he already sensed: the child had died. The king, who had refused food while the boy lived, did something that confused everyone. He rose. He washed. He changed his clothes. He went into God’s house and bowed. Only afterward did he come home and ask for food.

His servants were baffled. “While the child was alive, you fasted and wept,” they said. “Now that he is dead, you get up and eat.” David answered with a strange, clear peace that did not erase pain but framed it: while the child lived, there was hope God might yet relent, so he pleaded. Now the child was gone; the answer, however hard, was final. He could not bring the boy back, but he trusted he would one day go to where the child now was. Grief stayed, but despair did not own him. He chose to worship in the very place where his heart was breaking.

After the days of intense mourning, life moved in an unexpected direction. David went to Bathsheba, not as a secret visitor this time, but as her husband. He comforted her. Their shared loss had been born from his sin, yet now he drew near to her pain instead of hiding from it. In time she conceived again. Another son was born, and they named him Solomon. The text gives a quiet but stunning note: the Lord loved him. The same woman whose name entered Scripture through tragedy now became the mother of the son through whom God would continue His promise and through whose line, generations later, the Messiah would come.

The consequences Nathan had announced still played out in David’s wider family. Conflict, betrayal, and bloodshed would surface among his sons; the “sword” in his house would slice through relationships he cherished. His kingdom would never again be as simple or clean as in the days when he ran toward Goliath. Yet in the middle of this painful aftermath, two things remained true at the same time: David’s sin cost far more than he imagined, and God’s grace reached far deeper than he deserved.

David’s Journey: Summary

David’s life unfolds from humble shepherd boy to flawed king, marked by triumphs of faith and stumbles into sin. In the pastures, he defended sheep from lions and bears, honing courage and trust in God that later propelled him to fell Goliath in the Valley of Elah with a sling and stone. Anointed by Samuel yet hunted by Saul, he hid in caves like En Gedi, sparing his enemy’s life twice to honor God’s timing. As king in Jerusalem, he brought the ark home in a procession of sacrifices and danced with abandon in simple linen, prioritizing worship over dignity. Yet power led to his darkest hour: spotting Bathsheba bathing from his rooftop, he summoned and slept with her, then orchestrated her husband Uriah’s battlefield death to cover the pregnancy. Nathan’s parable exposed him “You are the man” prompting raw repentance in Psalm 51. Their first child died despite David’s fasting; Solomon followed, loved by God amid family strife that fulfilled Nathan’s prophecy of a “sword” in David’s house.

Key Lessons

Faith in obscurity prepares for visibility: Pasture battles against predators built David’s readiness for Goliath, proving small fidelities equip for giants.

Restraint defines true power: Caves taught him to spare Saul, contrasting the rooftop where unchecked desire destroyed lives.

Sin’s ripple effects endure: Adultery and murder brought family violence, child loss, and public shame, yet repentance invited restoration through Solomon’s line to the Messiah.

Worship exposes the heart: David’s ark dance showed joyful surrender; Michal’s scorn highlighted pride’s peril.

Grace confronts and restores: Nathan’s mirror led to confession, not condemnation forgiveness came, but so did consequences, modeling brokenness met by mercy.

David emerges not as flawless hero, but “a man after God’s own heart” through return amid failure his psalms and altars testify to a life that kept seeking the Shepherd who first found him.

David anointed while still with the sheep:

1 Samuel 16:1–13 – Samuel anoints David in Bethlehem while he is tending sheep.

David as a shepherd, lions and bears:

1 Samuel 17:34–36 – David tells Saul how he struck down a lion and a bear to rescue his father’s sheep.

David and Goliath in the Valley of Elah:

1 Samuel 17 (whole chapter) – the full David and Goliath narrative: Goliath’s challenge, David’s faith, and the victory with sling and stone.

David hiding in caves and sparing Saul:

1 Samuel 24 – David spares Saul in the cave at En Gedi, cutting off a corner of his robe.

1 Samuel 26 – David spares Saul a second time, taking his spear and water jug.

David becoming king and ruling from Jerusalem:

2 Samuel 2:1–7 – David becomes king over Judah.

2 Samuel 5:1–5 – David becomes king over all Israel.

2 Samuel 5:6–10 – David captures Jerusalem and makes it his capital.

David bringing the ark and dancing “undignified”:

2 Samuel 6:1–23 – first failed attempt, Uzzah’s death, then the successful procession; David dances before the Lord wearing a linen ephod; Michal despises him.

1 Chronicles 15–16 – parallel account of the ark being brought to Jerusalem and the worship that follows.

David and Bathsheba (the rooftop, adultery, Uriah’s death):

2 Samuel 11:1–27 – David stays in Jerusalem, sees Bathsheba, sleeps with her, arranges Uriah’s death, and takes her as wife.

Nathan’s parable and David’s repentance:

2 Samuel 12:1–15 – Nathan’s story of the rich man and the lamb, “You are the man,” David’s confession, prophecy of consequences, and the child’s illness.

2 Samuel 12:15–23 – the child’s death, David’s fasting, worship, and explanation to his servants.

Aftermath and Solomon’s birth:

2 Samuel 12:24–25 – David comforts Bathsheba; Solomon is born; the Lord loves him.

Psalms tied to this season of David’s life (for reflection, not narrative details):

Psalm 51 – traditionally linked to David’s repentance after Nathan confronted him.

Psalm 32 – often associated with confession and forgiveness in David’s experience.